Herbert Gleason isn't to be trifled with. Even when it comes to figuring out what makes him tick.

In one instant, he'll quote an oath every British monarch has sworn, "to sustain those things that are of good report." In the next, he'll rip off a self-deprecating monologue about his two-year stint as editor of the Patriot Ledger op-ed page preceding law school.

|

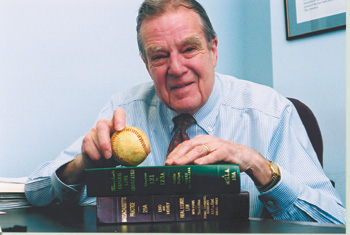

| Attorney Herbert Gleason has spent his career advocating for Boston neighborhoods. He says the ties that bind city neighbors are what sets Boston apart from other cities. |

Within that unpredictability, it could be argued, lies Gleason's strength as an attorney.

Equally incongruous is the 74-year-old solo practitioner's soft-spoken conversational tone. You'd half expect wide-eyed oration from the mouthpiece for successful efforts to save Fenway Park and to thwart Two Financial Center's monolithic insertion into the heart of a Boston historic district.

Instead, you get Bing Crosby. With a bite, of course.

"I don't take a lofty moral position," says Gleason, former corporation counsel for the city of Boston under Mayor Kevin White. "I do these things. Frequently, I get paid for them. I enjoy them. I enjoy law in the public sector more than any other kind of law. I'm passionately concerned about the environment of the city of Boston and preserving what's wonderful about it."

Gleason would know. Born in Roxbury, he is a 45-year resident of Beacon Hill. What sets Boston apart, insists Gleason, are the ties that bind the city's neighborhoods.

Attorney: Herbert Gleason

Years in practice: 45

Born: Roxbury, Mass.

Resides: Beacon Hill

Current location: 50 Congress St., Boston

Firm: Self

Law School: Harvard Law School, 1958

Undergraduate Studies: Harvard, 1950

Diploma: Western Reserve Academy (Ohio)

Specialty: Municipal law

Family: Wife, Nancy; son, David, 42; daughter, Alice, 39

Select work history: SJC law clerk, 1958-59; partner, Hill & Barlow, 1967-69; corporation counsel, city of Boston, 1968-79

|

It was neighborhood citizen action and organization that beat the Red Sox plans to forever alter the Fenway's environs by building a new ballpark. It was the same grassroots grit that tabled Two Financial Center earlier this year, which, as proposed, would have swallowed considerable portions of Boston's historic Leather District with an office tower topped by a 205-foot spire.

Gleason views his role in those endeavors as little more than steward. Boston's neighborhood pathos provided the steam.

"There are so many concerned citizens and concerned neighborhoods in Boston, it's marvelous," says Gleason. Referring to Robert Putnam's critically acclaimed 2000 book on social disengagement, he said, "I haven't read 'Bowling Alone,' but whoever wrote that book has never been to Boston. We're not bowling alone in this city. The neighborhood strength is incredible.

"When I served under Kevin White, there were only two organized neighborhoods," he adds. "East Boston was fighting the airport and Roxbury was advocating for better schooling. Now, they have a lot of company."

Like the Fenway.

"Herb certainly provided the gravitas and the expertise when Beacon Hill and Mayor Menino were trying to cobble together what amounted to a $1.5 billion subsidy for the Red Sox," says Boston's Peter Catalano, a founding organizer of the Fenway Action Coalition, which, along with the group Save Fenway Park, hired Gleason to spearhead legal opposition to a new ballpark.

"His advocacy and legal memos created an atmosphere that forced the interested parties to fold their tent. He helped turn public opinion. The decision to put the team up for sale (in October 2000) was clearly based upon a realization that a (new stadium deal) wouldn't go through."

Before Gleason moved to the Mayor's Office, he was a partner at the law firm Hill & Barlow. And though Gleason spent less than 12 years in the public sector, he still draws substantive satisfaction from that term of service that concluded nearly 25 years ago. He's most proud of the development of community health centers - an issue that continued to be important to him after he left the public sector as he served as director of Boston's nonprofit Neighborhood Health Plan from 1987 to 1998.

"I'm most pleased with the development of community health centers during that period (with Mayor White)," he says. "At that time, communities were organizing around the development of health centers. There were 24 community health centers created in that era and most of them are still flourishing. They currently provide care to about a third of the citizens of Boston."

And Gleason's civic affiliations don't end with neighborhood action. He is a founding organizer of the Lawyer's Alliance for World Security, which advocates for the containment of weapons of mass destruction through the vehicle of international law. He is a board member of the Massachusetts Apple Seed Center, an affiliate of the National Apple Seed Foundation, which searches for systemic approaches to public problems rather than case-by-case litigation. And he's been secretary of Boston's Health Action Forum since 1985.

But municipal law and its associated challenges in the 21st century engender Gleason's most pointed pronouncements.

"I think the biggest challenge facing Boston is making it a place that young families can stay," he says. "That dynamic raises issues on a number of fronts. Housing, schools and safety. Young families are getting priced out. And too many middle-class families want to live in the city, but opt out because they're looking for a better education for their children than they believe Boston public schools provide. We can do better on that score. We have to."